Ottoman Sephardic Genealogy: An Introduction

Page 2. by Dr. David Sheby

Continued...

Conversions tables for the first of the month in the Turkish-named Hejira calendar to the Gregorian calendar and first of the month of the fiscal calendar to Gregorian calendar can be found in:

Table 1.3: Programs and sources for Ottoman calendar conversions Hijri - Gregorian Dates

"COMPUTAS"

For those who cannot download the "Computas" program, a table of calendar equiavalents is in the monograph:

Birken, Andreas: Die Zeitrechnnung Handbuch der turkishchen Philatelie. Teil I: Osmanisches Reich. Arbeitsgemeinschaft Osmanisches Reich/Turkei, 1995, 40 pp. ISBN 3-931114-00-7. Bilingual (German and English).

Birken's text contains tables for the conversion of dates among the (a) Ottoman religious, (b) Ottoman civil/fiscal, and (c) Gregorian calendars. In addition, the Ottoman fiscal months' names are printed in osmanlica (page 9). Birken's monograph is available from: James Bendon Ltd., P. O. Box 56484, 3307, Limassol, Cyprus. Contact info as of April, 2001: E-mail: [email protected].

1.2.4 "Reading" the Birth Certificate

1.2.4 "Reading" the Birth Certificate: Month/Date Figure 1.1 reveals where specific information is located on the printed Ottoman birth certificate from the late 19 th and early 20 th centuries. The task is to decipher the handwritten entries which can be difficult to read. Dates are the one of the easier pieces of information to decipher. Figure 1.10 is a blow up of a section (i.e., top row, 4 th box from the right) of the Ottoman birth certificate shown in Figure 1.1. Using Figure 1.7's list of Arabic numerals the Ottoman year of 1320 is identified, as are the numerals "2" and "8" which correspond to a date in a month (to be identified).

Figure 1.10. The year (1320) and day (28) of month for the Ottoman birth certificate (Figure 1.1) are identified from the table of Arabic numerals in Figure 1.7.

Identification of the month is more difficult, but can be successful through detailed comparison of the date of birth box contents with each of the Ottoman months in Figure 1.9. In Figure 1.11 the month "Kanun-i-sani" is displayed twice so that it can easily be compared with different portions of the text. The letter sequences "SA-NY" (written here left to right, but written right to left in osmanlica as shown in Figure 1.11) are detected as is the sequence "K-A". No other month (Figure 1.9) has similar letter sequences. Hence the month is Kanun-i-sani. The Ottoman date is 28 Kanun-i-san 1320.

Figure 1.11: The month (for the date of birth in the Ottoman birth certificate of Figure 1.1) matches "Kanun-i-sani" (from Ottoman months in Figure 1.9). The resultant date 28 Kanun-i-sani 1320 is equivalent to 28 January 1905 (Julian) or 10 February 1905 (Gregorian).

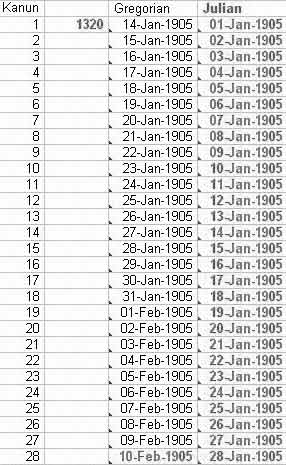

Using Birkin (1995) a table of equivalent dates in the Julian and Gregorian calendars can be constructed (Figure 1.12). Kanun-i-san 1320 is equivalent to 28 January 1905 (Julian) or 10 February 1905 (Gregorian).

Figure 1.12: Ottoman civil-Gregorian-Julian date equivalents for the first 28 days in Kanun-i-sani 1320 derived from Birken (1995, above).

1.3 Importance of Foreign Languages

The Sephardim's Ladino-culture embedded within the Turkish-speaking Islamic Ottoman Empire guarantees that genealogical-related source material will be encountered that will written in a variety of foreign languages, alphabets and script styles (cf. Table 1.4). Working with foreign languages is not a optional task for a dedicated Sephardic genealogist, but a necessity and a vehicle to obtain intimacy with a distant era.

Table 1.4: Languages and alphabets encountered during Sephardic genealogical research Latin letters with modern Turkish orthographic symbols. Useful for reading modern Turkish publications (such as academic publications on Ottoman-period studies) and identifying sites of tombstones (see below). Note: Turkish fonts are available at http://www.turkey.org/fonts/win311.htm Arabic alphabet with 3 additions, from Persian, for sounds like letter "p". Important for reading Ottoman birth certificates, passports, and other government prepared material. Official forms will be printed in a variety of lettering styles, and their entries will typically be handwritten in a manner difficult to decipher. Hebrew lettering: for reading tombstone & dedication inscriptions, and rabbinical responsa. Hebrew lettering is often used as the alphabet for transliterating Ladino text written in solitreo (or Rashi) into modern Hebrew for use, for example, in dictionaries. Rashi-style lettering: a font used for Ladino-language newspapers, and other printed material (books) Cursive script: solitreo: for reading late 19th century handwritten correspondence or notations on personal memorabilia Variant cursive scripts, close to but distinct from solitreo: used on kettubot (marriage contracts) and community lists from mid 19th century and earlier.

- The records of the Alliance Israélite Universelle (AIU).

- The Sephardic journals (French) ETSI and (Belgian) Los Muestros and other contemporary scholarly works (e.g., dictionaries) dealing with Ladino and Sephardic studies

The Cyrillic alphabet is used for writing Bulgarian and Serbian, the national languages for two successor states of the Ottoman Empire (Bulgaria and Serbia--formerly "Yugoslavia) 1.3.1 Modern Turkish Orthography

Familiarity with five letter forms in modern Turkish (Figure 1.13), without any ability to speak Turkish, can be helpful to a Sephardic genealogist.

After the establishment of the Republic of Turkey, in 1923, Arabic was abandoned as the alphabet for writing the Turkish language (1928). In its place, the Latin alphabet was adapted, with additional letters, for use with Turkish. The modern Turkish letters of most use to a Sephardic genealogist, due to their unique orthographic symbols are (Figure 1.13):

1) lower and upper case "c" with a "cedilla" (comma-shaped mark);

2) lower and upper case "g" with the curved diacritical mark "breve"

3) lower-case "i" without a dot;

4) upper case "i" with a dot;

5) lower and upper case "s" with a "cedilla".

Figure 1.13 Modern Turkish Alphabet

Modern Turkish Alphabet

The following two examples illustrate how elemental knowledge of modern Turkish orthography can be useful to a SG.

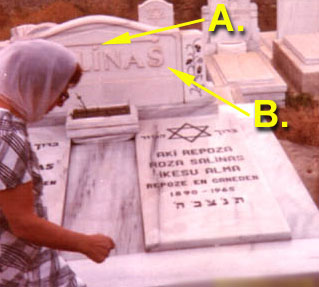

1.3.2 Example 1: Location of a Grave Site

A SG posted an inquiry, then a photograph, to a Sephardic mailing list. It was an inscription on a relative's gravesite, showing that the epitaph which was written in Ladino, in Latin letters. The SG inquired if the tombstone inscription might identify the country of burial, i.e., where the grave was located. The spelling containing the Latin letter "z". Because of the presence of Ladino in Latin letters, it was speculated that the grave was either in the United States or in a Latin American country.

After publication of a photograph of the entire gravesite area, a list-member noticed that the family name was written using the capital I with a dot over it: an orthographic (spelling) unique to modern Turkish as shown in Figure 1.14. Knowledge that this spelling innovation occurred in Turkey in 1928 (and that Turkey's international borders were fixed by treaty in 1923) allowed the grave's location to be fixed within the borders of the modern Republic of Turkey.

Figure 1.14 SALINAS family plot in unknown Turkish cemetery. Circa 1970. (Source: Adatto/Alfassa/Benson/Yerushalmi family)

A. Note the dot over the capital letter "I". This is an indication of modern Turkish orthography (spelling) and the location of the tombstone (burial site).

B. Note that the surname SALINAS was spelled in all capital letters.

Continue to Page 3.